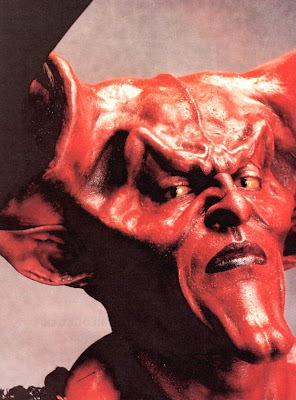

“. . . If he were beautifulAs he is hideous now, and yet did dareTo scowl upon his Maker, well from himMay all our misery flow. Ph, what a sight!”Dante, InfernoAccording to

The Rolling Stones, we live in a period of history where the Devil is so inconspicuous he needs to introduce himself. After all, would you really notice if the Evil One was your neighbor or your math teacher or your beloved Prime Minister / President? I know I wouldn’t: they all look equally suspicious to me.

Bad jokes and religious beliefs aside, the concept of a being that embodies all human corruption and whose main goal is to destroy all goodness in the world is so deeply ingrained in our collective subconscious that we tend to take it for granted and ignore the subtleties and complex moral dilemmas it really stands for.

The belief in demons is as old as mankind. The Judeo-Christian Satan or Devil – the “popular” horned, tailed, winged fallen angel who rules over Hell – has his roots in antecedents such as Tryphon, Set, and other sinister deities of the ancient Egyptians, as well as the evil spirit Ahriman from the Persian dualistic system.

The concept of the Devil has also gone through several evolutionary phases by the way of Christian literature, including various writings and readings of the Bible. It took learned Christians quite a while to determine that it was the same Satan or Lucifer, Son of Morning, that lured Adam and Eve and tempted Christ. It took them longer – about 12 centuries, in fact – to agree that Satan was emperor of Hell and ruled an appropriate court hierarchy. Other parts of the myth would continue to be added even further down the road, mostly through poetry and visual arts – the pitchfork, for example, is a product of 19th century poster art.

Of course, my favorite visual depiction of the Devil and his Hell comes from Dante’s

Inferno. What is more striking than a winged giant frozen waist-deep in a lake of ice, trapped at the Earth’s core, forever grinding the worst of human traitors such as Brutus, Cassius and Judas Iscariot? The French artist

Gustave Dore made a brilliant rendering of this image in the 19th century, and I can bet that even as we speak there is an aspiring metal band that is trying to express it through music in some forlorn garage.

What makes the Devil so appealing and scary as an idea, however, is not so much his grotesqueness as much as his power to corrupt, which is why the story of

Faust and all other versions thereof have always fascinated me.

The basic story of Faust goes something like this: Faustus, a scholar of Wittenberg desires more knowledge and power so he makes a pact with the Devil, whereby all his wishes are to be granted for 24 years in exchange for his soul. Faustus does gain knowledge and power but he spends most of his time frivolously, playing jokes on the Holy Roman Emperor and on the pope, and resurrecting Helen of Troy. In the end, he meets a hideous doom within earshot of other scholars, who, when they break into the room, find only bloody traces.

Goethe greatly expands the plot, particularly by giving Faust the chance to redeem himself, but the basic idea of corruption remains at the heart of the story.

Interestingly,

Johannes Faust was a real person. He performed tricks, gained a reputation for prophecy, and claimed that his powers came from the Devil, the best proof of which seems to be that he somehow escaped the stake. His claims of demonism were taken at face value, and, as soon as he was dead, fanciful publications called

Faustbuchs began to appear relating to stories of his adventures, told in such a way as to incorporate stories formerly told about Roger Bacon and Pope Sylvester II.

Basically, all stories about the Devil worth their salt are variations on the Faust theme. Films such as

Rosemary’s Baby and

Angel Heart first come to mind for the obvious reasons but the theme could be stretched all the way to

William Golding’s literary masterpiece

Lord of the Flies where the pact and the subsequent corruption are implicit. The most intriguing Devil concept, however, is presented in

Clive Barker’s

Hellraiser: the idea that devils and angels, hell and heaven, are one and the same rings true on so many levels, it positively reeks of humanity.

On the other hand, stories where the Devil is merely an evil entity that openly confronts the main characters aren’t devil stories at all – I’d much rather view these as monster movies where the monster takes the shape of the Evil One.

The Omen is an example of this:

Damien could easily be some sort of super-vampire as he poses little to none moral questions on his way to destroy the world, or differently put, the film asks the viewer to be afraid of being killed, not of being tricked into becoming a monster. I’m still undecided on what

The Exorcist is, but if you press me hard, I’d say it’s a vampire film, as well, since it’s just a thinly veiled allegory of sexual awakening.

Finally, let’s get back to The Rolling Stones and the Devil’s introduction. Ever since the renaissance, the Devil has been presented chiefly as a perfect human being, which, of course, makes it much easier for him to create pacts and buy out souls. You’d run from a red-skinned triple-horned monster but not from naked Angelina Jollie / Brad Pitt, would you? This is what, at the end of the day, makes the concept of the Devil so scary: corruption is not a threat that one can kill or banish like other monsters but rather a constant threat one has to learn to live with and fight off on regular basis, which is extremely hard once you take into account all those deeply corrupted people around you that flash their ill-gained money and power along with, you know, their golden crucifixes.

A word or two about the music in this episode: including The Rolling Stones would have been way too easy, don't you think? The Laibach version of "Sympathy for the Devil" included is much more fun and it certainly meshes better with the two versions of "Ave Satani" that follow. The hit of the night, however, goes to Buck Owens and his "Satan's Got to Get Along without Me". Enjoy!

...and that's not all! We've added a little bonus here: the trailer to the videogame Dante's Inferno, just so you know what gamer delights you might have been missing, he-he... 'Till next episode, then!